Soy Sauce Masters

At the Crossroads between Tradition and Innovation

Lynn Su / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Phil Newell

February 2025

The traditional method for making soy sauce is to first steam soybeans, then stir in kōji mold and wait for a few days for the mold to penetrate the beans, then place the beans into vats and blend in salt or add salt water. After long exposure of the vats to sunshine, the contents are removed and undergo filtration and pressing. Then the resulting sauce is cooked in a pot and finally bottled for sale to the public.

This production process is broadly similar at different manufacturers, but the details differ, creating clear distinctions between makers.

With the industrialization of food production, rapid brewing methods have been invented for soy sauce. However, since various food safety scandals, consumers today are more conscious about the quality and sourcing of ingredients. As large manufacturers have begun to come out with pure-brewed soy sauces, many quality-oriented small makers have also attracted attention. Let’s see how they define good soy sauce.

“The key to making soy sauce is in the cooking stage.” —Hsieh Yi-che

Yu-Ding-Shing: The appeal of wood fires

Yu-Ding-Shing, located in Xiluo, Yunlin County, traces its brewing technique back to Wuan Chuang Soy Sauce, which also calls Yunlin home. Yu-Ding-Shing’s business was in decline until brothers Hsieh I-cheng and Hsieh Yi-che, of the family’s third generation, returned home and turned the firm towards high-quality soy sauce. Yu-Ding-Shing prides itself on the critical process of “cooking” the sauce over a wood fire.

Entering the rural factory, a sweet fragrance floats in the air. Inside, brewed sauce is being heated in large stainless-steel stockpots over wood fires. Hsieh Yi-che and his father, Xie Yudu, prefer wood fire to high-efficiency gas burners for two reasons: Firstly, it lowers costs. Secondly, the longer cooking time improves the aroma of the soy sauce. However, master brewers must control the strength of the fire while at the same time continually stirring the sauce to avoid it burning on the bottom of the pot. Xie Yudu says that when the sauce reaches a full boil the fire must be reduced to a minimum level to avoid losing the aroma.

Yu-Ding-Shing, which combines old and new, also experiments with adding flavors to their soy sauce. With pineapple added, it has a fruity fragrance and can be used as sukiyaki sauce. With bamboo salt mixed in, there is a mild scent of smoked plums and it is well suited as a seafood condiment. Meanwhile sugar syrup made with sugar from the local Huwei Sugar Refinery brings a caramel color and a bright sugarcane aroma. It is perhaps this innovative thinking that keeps customers loyal to Yu-Ding-Shing.

Yu-Ding-Shing’s second-generation boss Xie Yudu stirs “fresh soybean juice” with a practiced hand in order to prevent burning.

Yu-Ding-Shing prides itself on using wood fires in the step known as “cooking” (reheating) the soy sauce.

Wan Feng Soy Sauce: Attention to detail

Expressing the making of soy sauce in terms of painting, the raw materials are the pigments, while fermentation with kōji mold is the execution of the painting itself, and cooking is the refinement of the work’s details. A majority of soy sauce makers say that kōji fermentation is the most important step in shaping the flavor of soy sauce.

Wu Kuo-pin, the third-generation boss of Wan Feng Soy Sauce in Douliu, Yunlin County, has concluded from his experience that “the flavor of soy sauce is determined primarily by kōji fermentation and secondarily by cooking.”

It is a cool winter’s day, the slow season in soy sauce manufacturing, but Wu is not idle, using this time to do experiments. The factory, located behind a private house, includes his laboratory.

Wu used to work in the high-tech sector, but resigned due to poor health from overwork. He returned home to recuperate, and began to be careful about his diet. After taking a short course in organic farming, he persuaded his family to let him take over their soy sauce business, which at the time was being run by his grandfather and uncle.

With a background in science and engineering, in addition to benefiting from his elders’ advice, he has sought confirmation in science. However, he adds that there are aspects of tradition that he doesn’t want to change.

He insists on using traditional steamers rather than pressure cookers to steam his soybeans. He is also meticulous about where his ceramic vats are placed to be exposed to sunshine. He explains that the fermentation activity of kōji mold declines greatly at temperatures above 45℃, and stops altogether at 55℃. Therefore, rather than having his vats stand on concrete, he places them on grass, which takes more effort to maintain but modulates the temperature.

Wan Feng is a venerable old firm that is one of the very few still continuing to use dry brewing. Though this method yields less soy sauce, its product’s flavor is characterized by strong notes of dried mustard greens, alcohol, or chocolate. This is the “old-time flavor” that Wu was finally able to replicate after much painstaking effort.

We listen as Wu enthusiastically explains each step in the soy sauce making process, and describes how the benefits of organic food ingredients that restored him to health have made him believe even more strongly in choosing premium raw materials. He is the embodiment of the old adage that “ingenuity in varying tactics depends on mother wit.” As a master soy sauce maker, his mind is always on the details.

“The flavor of soy sauce is determined primarily by fermentation with koji mold, and secondarily by cooking.” —Wu Kuo-pin

Yu-Ding-Shing has a variety of products that are convenient for use by contemporary consumers.

Rich and fragrant “fresh soybean juice” that oozes up when a hole is dug in fermented soybeans is known as “bottom of the pot sauce.”

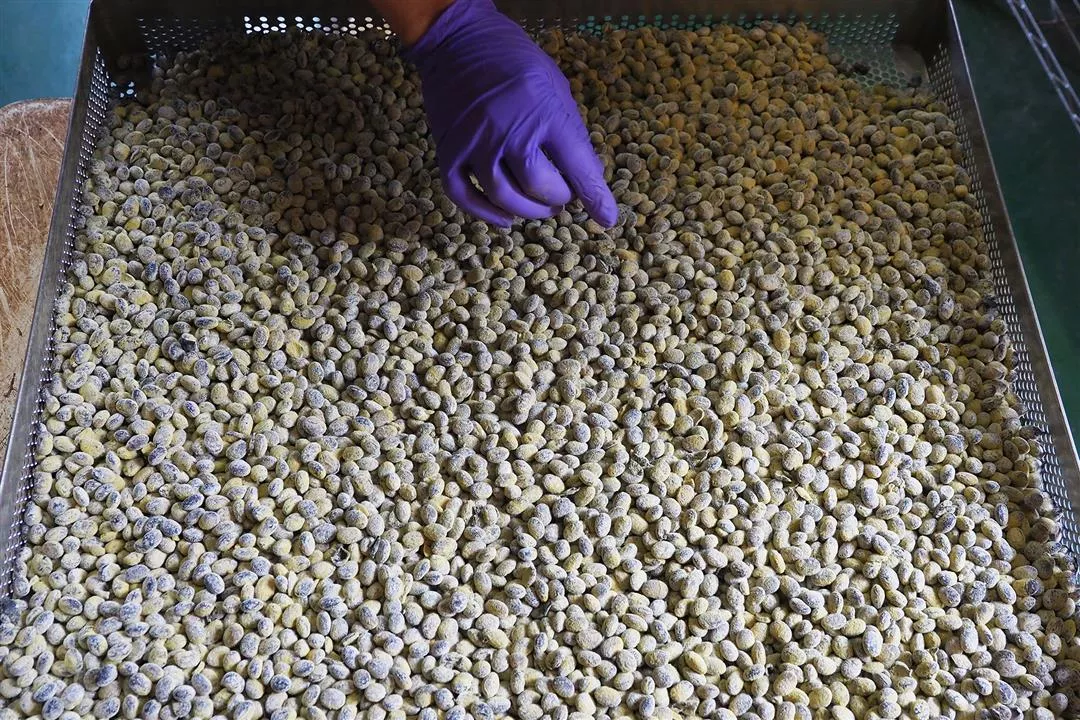

Soybeans fermented with koji mold play an important role in shaping the flavor of soy sauce.

Wan Feng Soy Sauce sets its vats out in a field by a river, where the moisture in the air ensures that the liquid in the vats does not evaporate too rapidly while grass ameliorates the temperature. The entire area forms a microclimate suited to brewing good soy sauce.

Wu Kuo-pin, who likes experimenting, has made not only the commonly seen black bean soy sauce but also soy sauces with flavorings including roses, mountain litsea, and herbs, which can be used for making sweets.

Royal Jade: Growing beans to brew soy sauce

We arrive in Pingtung County in Southern Taiwan. Its Neipu Township is home to the major soy sauce manufacturer Wan Ja Shan and also where the low-sodium soy sauce developed by National Pingtung University of Science and Technology is produced. Xinyuan Township, at the other end of Pingtung, is the location of Royal Jade, a soy sauce maker founded in 2015 that has enjoyed rapid growth. Even food expert Hsu Zong says: “I’ve become entranced by this soy sauce.”

Unlike most small soy sauce company owners, who have inherited the family firm, Royal Jade founder Brian Chien made a huge shift in profession from the electronics industry. His reasons for returning to his rural hometown to open his soy sauce firm were simple: Firstly, he wanted to look after his parents. Secondly, he was eager to run a business of his own.

Stopping at Chien’s new factory in Xinyuan, besides the large open-air vat area, the super-clean plant has a full panoply of equipment, from automated steamers and presses to kōji fermentation and bottling facilities. In addition, in neighboring Wandan Township, Chien has rented 60‡70 hectares of farmland which is also part of his enterprise.

不受歷史遺留束縛的皇玉醬油不僅借鏡了科學的釀造方法,也是國內少有的自種醬油原料的醬油業者。錢先生喜歡親自動手,他60%的時間都花在了農事上。他也培育了兩個新的大豆品種-禦玉1號和2號,以避免植物品種權利問題。他甚至培養並繁殖了自己的麴菌。

對錢先生來說,釀造醬油最重要的元素是原料。這可能是因為他剛進入釀酒領域時,受到了酒精生產的影響。他說,不同品種的葡萄可以釀造出截然不同的葡萄酒風味,因此可以說原料是口感的基礎。 “製作醬油的三大要素——原料、曲霉發酵、時間——我認為原料是最重要的。”

錢先生和他的妻子蘇和琳一起解釋說,他們自己種植大豆的原因不僅僅是為了獲得更好的新鮮度。他們選擇下田耕作的另一個原因是,在他們創業之初,市場上以有機或環保方式種植的大豆很少,而且價格昂貴,因此夫妻倆決定透過自己種植來尋求原材料供應的自主權。

而且,「只有原料和釀造技術兩個面向同時進行,才能生產出具有當地風土特色的獨特醬油」。如果我們按照日本醬油協會列出的各種類別來查看Royal Jade的產品——包括老抽(koikuchi)、淡抽(usukuchi)、白醬油、醬油和黑豆醬油——那麼根據原料的不同,所有產品都有不同的風味。

他們的產品有重現傳統口味的,也有嘗試新口味的。蘇和林說,作為第一代釀酒師,他們清楚知道自己站在傳統與創新的十字路口」。在他們的工作中,至關重要的那顆小大豆不僅是醬油的起點,也代表著「堅守信念」。

“In brewing soy sauce, the most important thing is the ingredients.” —Brian Chien

Brian Chien, who is intrigued by farming, not only has taken pleasure in breeding work, but the fragrant rice he cultivates with the Kaohsiung No. 147 cultivar has been named champion rice, with taste evaluations exceeding 80.

Brian Chien personally cultivates yeast, lactic acid bacteria, and koji mold, and he takes advantage of the unique characteristics of each when fermenting his ingredients. The photo shows koji-fermented soybeans, covered in yellow-green spores, waiting to be placed in a vat.

The categories of products made by Royal Jade are distinguished by the ingredients used.

Helin Su (left) says that their company name combines the Chinese character for “royal” (to indicate “the highest level”) with the character for a kind of jade emblem used in ancient times by officials in charge of transporting grain. Using scientific methods, they aim to promote soy sauce craftsmanship to the highest level.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)