Global Outreach for Sustainable Development:

Taiwan’s University Social Responsibility Programs

Cindy Li / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Phil Newell

January 2025

University education is expanding from the classroom to promote sustainable development in local communities and even overseas. The photo shows students in the Engineering in Action (EiA) program at National Taiwan University of Science and Technology using their technical skills to repair electrical appliances for community residents. (courtesy of NTUST)

The world-famous primatologist Jane Goodall has said: “My greatest hope is our young people.” This was the motivation for her Roots & Shoots youth action program, and many educators share her belief that through education, the next generation can play a critical role in sustainability.

Taiwan’s university social responsibility (USR) program encourages universities to use expert knowledge to help solve local problems. Emilio Tseng Yung-ping, vice president of National Chi Nan University, says, “USR has become part of our university’s DNA.”

National Chi Nan University

In the devastating earthquake of September 21, 1999, two-thirds of the buildings at National Chi Nan University (NCNU), then only four years old, were damaged. Then-president Dr. Lee Chia-tung decided that some students should relocate to Northern Taiwan for classes, little thinking that this would lead to a misunderstanding between the school and local residents that would last for a decade.

Thus even before the Ministry of Education began promoting its national USR Program in 2018, NCNU was already deeply involved in local affairs, with USR projects of its own spread all across Nantou County.

Under one of these—the “Shuishalian” environmental sustainability and skills training program launched by the NCNU College of Science and Technology (CST)—the university worked with the Sunrise Charity Organization and the Toyu branch of the Rotary Club of Taichung to extend its USR activities to Cambodia.

To assess the effectiveness of their slow sand filter water purification system, the team from NCNU brought instruments with them to test the pH value, turbidity, and microbial load of local water, and brought back samples to Taiwan to be tested for heavy metals. (courtesy of NCNU)

Matching technology to needs

Li Cheng-huang, chairman of Sunrise Charity, reveals that through Tseng Yung-ping he contacted a team from the CST about setting up a water purification system for Kanha Primary School.

Chen Ku-fan, a distinguished professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at NCNU, opted for a slow sand filtration system, mainly because it is easy to build and maintain. “They only need to regularly clean the sand at the top. Unlike a rapid filter, a slow sand filter doesn’t need additional chemicals or electricity, so it better meets local conditions”

In September of 2017 the team visited the locality, bringing their preliminary design drawings with them, and they tested the water quality and sought out suitable materials. Chen recalls: “The main problem was that we couldn’t find quartz sand.” They finally discovered this type of sand, which filters out microorganisms from water, in an aquarium shop. However, the appearance of the sand they found was different from what they were used to in Taiwan, and they worried it might be less effective. Fortunately, tests carried out upon completion of the project found no coliform bacteria, thereby meeting Cambodian standards for drinking water.

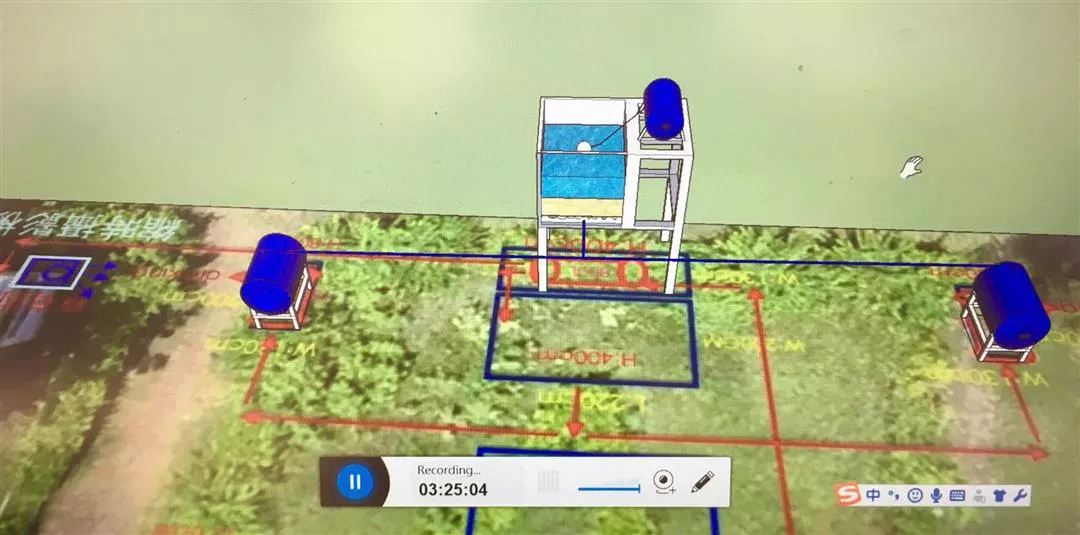

Faculty and students from the College of Science and Technology at National Chi Nan University designed a water purification system for Kanha Primary School in Cambodia that is adapted to local conditions. (courtesy of NCNU)

A sense of achievement

The filtration system built for Kanha Primary School also provides water for 1,500 nearby residents. Chen notes that it was only when students from Taiwan arrived in Cambodia that they understood the importance of United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, and saw practical aspects of implementation that they had never seen before.

Although for various reasons the team has been unable to return to the school, they have still guided their students in researching ways to use stainless steel tanks instead of concrete structures to filter the water. The steel tanks are easier to install and more versatile.

Chen reveals that in the future they want to introduce Taiwan’s experience in treating agricultural waste to Vietnam and so extend the Shuishalian program to more countries. Although there is no way to quantify the benefits of this program to students, he says: “They get a sense of accomplishment from seeing the textbook theories put into practice.” This is not achievable through classroom education in Taiwan.

Wang Meng-jiy says that despite extensive prior planning in Taiwan, there are always challenges when implementing projects overseas, to which students deftly adapt through communication and coordination. (courtesy of NTUST)

TaiwanTech

Wang Chiu-yen, a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at National Taiwan University of Science and Technology (NTUST, a.k.a. TaiwanTech) and one of the directors of its “Engineering in Action” (EiA) program, feels that the changes wrought in students by their involvement in international USR projects “can only be experienced in their specific time and place.”

The EiA program, inspired by Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders), is the longest-running USR program at TaiwanTech. Since 2005 the school has hosted many foreign students in its English-language graduate programs, and those from Southeast Asia identify most closely with the EiA’s ideals. Meanwhile, overseas universities have worked with the EiA program to bring change to communities in places like Surabaya, Indonesia and Can Tho, Vietnam.

EiA program participants have in recent years worked with the Osaka Institute of Technology to help revitalize Kawakami Village in Japan’s Nagano Prefecture by combining industry with innovative tourism. (courtesy of NTUST)

Learning from the unexpected

Before heading off to foreign lands, students must spend three to four months videoconferencing with their overseas counterparts. They repeatedly discuss and analyze local needs in order to devise a feasible project.

However, despite such intensive preparation, unexpected issues often arise. For example, in a project to build an aquaponic fish and vegetable farming system in Magetan Regency in Surabaya, the lead instructor, Professor Wang Meng-jiy of NTUST’s Department of Chemical Engineering, discovered a leak in the waterproof fabric lining during the sewing process. She anxiously waited for the students to notice the fault themselves, but finally had to point it out to them.

However, it was up to the students to determine the solution. “They said they wanted to change to another type of fabric, but it would take two weeks before they could buy the new cloth, and there was no time.” Wang Meng-jiy says that such unexpected developments are a valuable test for students.

Especially because the local language was not English, lots of coordination was needed for communication and purchasing. The students also had to finish the project on time without reducing its quality. Wang Meng-jiy says with a smile: “The engineers’ responsibility to deliver a finished product by the deadline definitely caused discussions to become heated.” But the students never saw giving up as an option.

Besides international projects, in recent years teams from Taiwan Tech have worked in remote indigenous communities in Taiwan’s Yilan County to address local issues and care for the land through practical action. (courtesy of NTUST)

Growth beyond the classroom

These engineers working outside the ivory tower not only offer sustainability solutions to the international community, they also interact with local students, teachers, and residents, creating precious memories.

Despite the difficulties—four months of pre-project planning, balancing classwork with project meetings, studying a new foreign language in a short time, and spending summer vacation working overseas in relatively primitive conditions—each year quite a few students sign up for EiA.

Perhaps this is because the impact on the students far outweighs the number of credits they receive for the program. As Wang Chiu-yen says, none of their USR programs are simply about one-way volunteer assistance to others, but all offer growth to both sides involved.

Teaching students in Eswatini to sew their own reusable menstrual pads is just the starting point for Sindi Shongwe. She hopes that in the future she can continue to leverage resources and generosity from Taiwan to bring substantive change to her homeland.

Chang Jung Christian University

“Students from Africa have told me that their dream is to change their societies,” says Kan Ling-hua, CEO and liaison officer for community sustainability at the International College of Chang Jung Christian University (CJCU). Kan sees USR programs, their dreams can become reality.

Benica Evarist Nziku, a student from Tanzania, came to Taiwan after being recommended by her local Jane Goodall Institute. Kan Ling-hua recalls that Nziku, inspired by the independence and autonomy of women in Taiwan, aims to promote women’s empowerment in her homeland. “In her first year at CJCU she proposed a program for Menstrual Hygiene Day.” She later launched the “Care Program.”

Combining gender education with environmental protection, Nziku and her partners started workshops to teach women how to sew reusable menstrual pads and inform people about women’s biology, in order to reduce period poverty and eradicate the stigma of menstruation. Starting from initial projects in communities around CJCU and building on the Taiwan experience, they have held over 30 workshops in Tanzania, Burundi, Uganda, and Eswatini.

Inspired by Benica Nziku, Sindi Shongwe from Eswatini introduced the Care Program to her own homeland. Shongwe says that the program is targeted not only at women but men as well. She and her partners collaborated with CJCU’s Department of Nursing to incorporate more material about women’s biology and health into the January 2024 CJCU workshop curriculum in Eswatini.

Through participation in University Social Responsibility programs, overseas students not only learn diverse skills, but are prompted to think about how they can apply what they have learned in school to improving their homelands. (courtesy of CJCU)

Seeds of hope from Taiwan

Abel Tuyisabe from Burundi, now in Taiwan for his fourth year, has diligently taken advantage of practical learning opportunities in Taiwan in areas such as biochar, care programs, and keyhole gardening, while considering how to implement such programs at home, especially in sustainable agriculture.

Tuyisabe explains that 90% of people in Burundi make their living in the agricultural sector. However, after long years of chemical-based farming, the land is unable to produce abundant harvests. In response he has introduced biochar technology to his homeland to help farmers pursue environmental protection as well as economic wellbeing.

Another of his goals is to promote keyhole gardens. Not only are they cheap to build, they require minimal amounts of labor, water, and fertilizer, and can produce good harvests year after year even in Africa’s inhospitable environment. On an internship back in Africa, he excitedly helped his cousin create the first keyhole garden in his hometown.

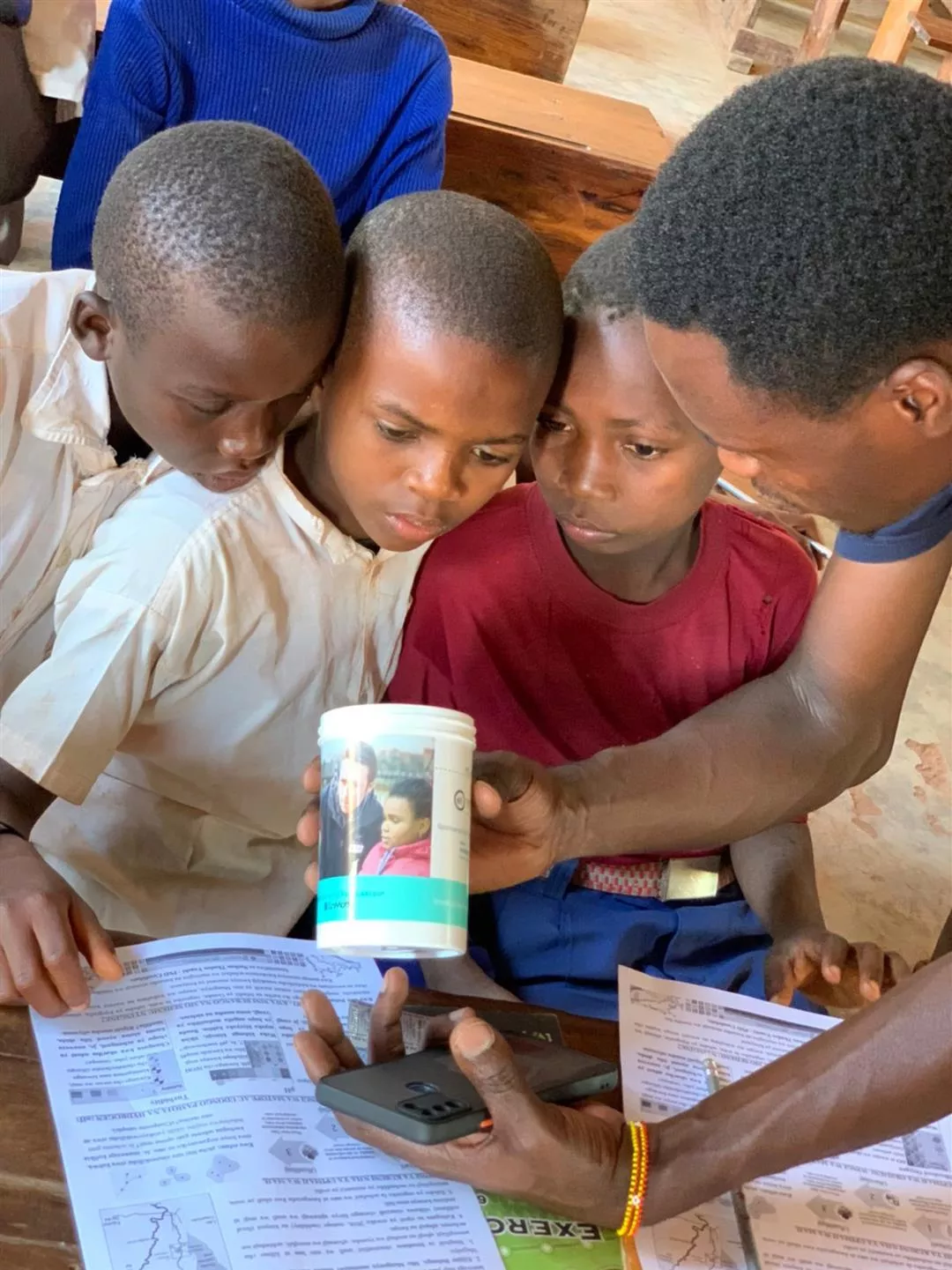

In addition, based on his observations of life in Taiwan, Tuyisabe decided to start a program for health stations in his homeland. He proposed a project to a local government there to teach people basic medical and health knowledge and use testing to help local people rapidly detect diseases—especially malaria—and get treatment. He says that many children die because people do not have thermometers and so don’t know when a child has a fever, a classic symptom of malaria, with the result that the child isn’t taken to see a doctor early enough.

These international USR programs also have an impact in Taiwan. Kan Ling-hua says: “When Taiwanese students hear the stories of these foreign students, they become more determined about their own paths in life.” Through these programs, seeds of hope continue to be sown.

By taking sustainability solutions learned in Taiwan back home with them, students from Africa can realize their dreams of contributing to their native countries. The photo shows students from the International Program for Sustainable Development (IPSD) at Chang Jung Christian University holding a workshop in Tanzania in 2022. (courtesy of CJCU)

Things we take for granted in Taiwan can offer new opportunities for promoting sustainable development in African countries. The photo shows a student from the IPSD at CJCU teaching children in Kigoma, Tanzania about water quality testing. (courtesy of CJCU)

Although students and faculty from NCNU have been unable to return to Cambodia in recent years, they have continued their efforts to optimize the construction of slow sand filter systems in order to better meet local needs.

The diverse origins of participants in the EiA program at NTUST enable those with backgrounds in the sciences and the humanities to collaborate to produce outstanding results that are both cutting edge and meet local needs. The photo shows the construction of an information wall in Indonesia’s East Java Province by a team from TaiwanTech. (courtesy of NTUST)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)