Governing Taiwan A Retrospective in the Year of the First Gubernatorial Election

Wang Chin / tr. by Phil Newell

December 1994

From the period of the Dutch occupation of Taiwan, through rule by Cheng Cheng-kung, Ching dynasty governors, and Japanese colonial governors-general, to the various types of governors of the post-WW II Republic of China, Taiwan has had 164 different executives over its 400 years of recorded history. Looking back on these chiefs, of course many were dedicated to their work. But there were also more than a few without the least accomplishment to their names. Today, in the midst of the first-ever popular election for the governor of Taiwan, let's go all the way back to the Dutch era of the 17th century and look at what all of those who have held governing power in Taiwan have done.

Of course it's taking the narrow view to say that Taiwan has "only" 400 years of history. After all, artifacts show that there were people living in Taiwan as early as 5000 years before the birth of Christ. In general, the main reason for the idea that Taiwan has only 400 years of history--except for its implications as a political statement--is because this is the shorthand way of referring to the available historical records. Though there were people here as far back as 7000 years ago, sadly they left no written records for us to study. Thus for the time being we leave aside the indigenous people's history and take the "discovery" of Taiwan by the Dutch as our starting point. This also happens to have been the time when Han Chinese began coming over from the mainland to Taiwan in large numbers. These developments caused Taiwan to suddenly "pop up" on world maps in the 17th century.

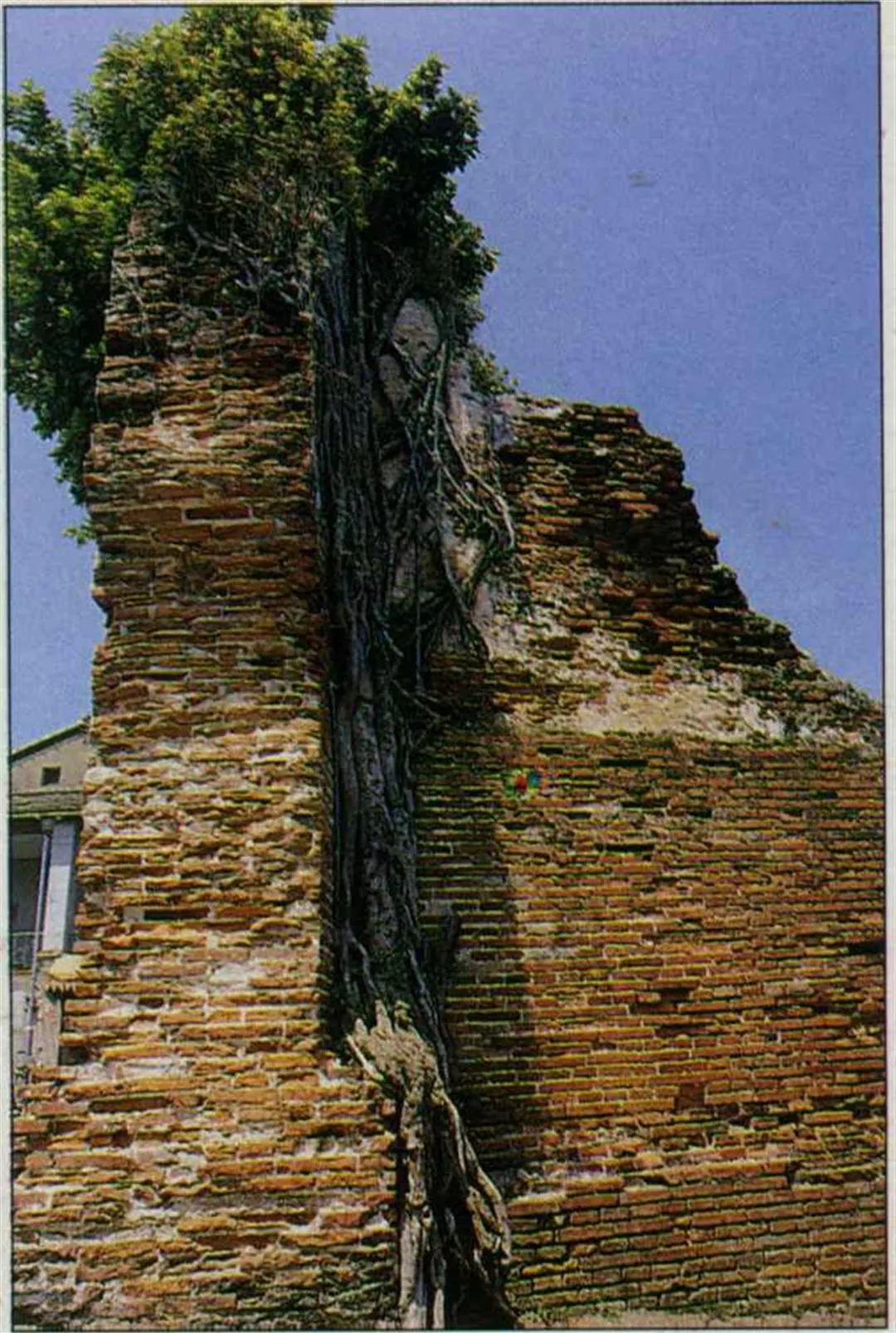

"Fort Zeelandia," built by the Dutch in the 17th century, had full defenses; the fort held out for a year before surrendering to besieging forces under Chinese general Cheng Cheng-kung.(courtesy of the Southern Meterials Center)

If you can't have the Pescadores...

We start with the odd fact that the Dutch only came to Taiwan by accident. To explain this point, we have to begin with the establishment of the Dutch East Indies Company.

Under the impetus of the Portuguese occupation of Macao and the monopolization of profits there, the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies Company in Java (in modern Indonesia) in 1602. The Company was given full authority to raise troops, declare war, appoint and dismiss officials, and to rule the colonies. This was one of the first forms taken by Western imperialism.

In July of 1603, the Dutch took over the Pescadores, but withdrew after being warned off by the Ming dynasty. The Dutch returned for a second attempt in 1622. After eight months of fighting and negotiating with the Ming, the Dutch gained a tacit admission from the Chinese side that Taiwan was beyond its sovereignty; the Dutch consequently left the Pescadores and came to Taiwan in 1624. The occupiers first built a wood and mud fort; in 1627 they constructed "Fort Zeelandia" (now "Fort Anping") out of brick and stone.

Taiwan was at first under the jurisdiction of the Dutch East Indies Company, under the formal title of the "Taiwan Branch Office" of the Company. The main goal of the occupiers was to undertake trade with China and Japan. Exports included deer skins, sugar, rice, and medicinal products, while imports included raw silk, gold, porcelain, and cloth. At that time the governor was appointed by the Company's central offices in Batavia, Java. There were 12 different governors during the 38-year period of Dutch occupation.

Although the Dutch did not rule Taiwan for very long, nor did their control extend very far, their introduction of modern concepts of property ownership had a far-reaching effect. For example, they established a type of "royal demesne" system, with registration of land ownership, and then recruited Han Chinese from the mainland to come pioneer and develop the land. The colonizers also established a basic tax collection system.

The Dutch, who landed in southern Taiwan, were not the only ones to establish their rule on the island in the early 17th century. The Spanish occupied Keelung, in northern Taiwan, in 1626, and set up an administration there. Due to a scarcity of historical documents, we only know that the Spanish occupied Tanshui in 1628 and installed a garrison there. Between 1626 and 1640, there were eight Spanish governors, who divided their time between Keelung and Tanshui. The Spanish were chased back to the Philippines by the Dutch in 1642.

Fort Zeelandia was renamed Fort Anping. The history of 400 years of governing in Taiwan is left behind in both the written word and historic artifacts.

The end of colonial rule

Frederick Coyett, the last Dutch governor, took up his post in 1656. In March of 1661 the Ming dynasty general Cheng Cheng-kung laid siege to Fort Zeelandia. Though the Dutch held out until February of the following year, unable to hold off Cheng's forces, the bastion surrendered.

After taking over in Taiwan, Cheng Cheng-kung converted the Dutch administrative offices into a royal court. Calling for "counterattacking the Ching" (who had just conquered the Ming), Cheng declared Taiwan the "Eastern Capital." The Cheng regime lasted through three rulers--Cheng Cheng-kung, Cheng Ching, and Cheng Ko-hsia--who were all called the "Duke of Yenping." The bureaucratic structure followed the Ming system. In terms of land management, besides continuing the "royal demesne" system, the "garrison field system" was adopted. Under this system, in ordinary times soldiers would farm the land and be self-sufficient. This saved the government money, gave the soldiers land to farm, established a sound foundation for agriculture, and even led to major accomplishments in terms of economic activities important to the daily life of the people (such as salt and sugar production, water conservancy, and paddy cultivation). Also worthy of note is that Taiwan already had developed external trade, exchanging goods with Japan and Western colonial possessions. In Western trade records, Cheng Cheng-kung is referred to as the "King of Formosa."

As far as Han Chinese are concerned, of course, the Cheng Cheng-kung interregnum was one of great success. But from the point of view of the aboriginal peoples of Taiwan, it was simply another colonial regime. The difference between Cheng and the Dutch was that Cheng came with 50,000 Han Chinese settlers. The Dutch, who had only a few thousand men, held meetings with the aboriginal chiefs in order to maintain peace. Cheng, on the other hand, completely shattered the organized society of the Pingpu aborigines. (The term Pingpu, which refers to aborigines of Taiwan's western plain, was adopted by the Japanese in 1935 to replace the deprecating terms--such as "barbarians"--previously used by Han Chinese to refer to the indigenous people.) The Pingpu were either massacred or assimilated into Han society through intermarriage, so that modern Pingpu have almost completely lost touch with their roots.

In the latter period, the Cheng court began to disintegrate, and internal struggles gave the Ching dynasty its chance. In 1683, the Ching official Shih Lang conquered Taiwan when Cheng Ko-hsia surrendered without a fight. Originally Cheng had hoped to be recognized as the Lord of Taiwan, and to rule peacefully under Ching suzerainty. But the Ching dynasty showed no mercy.

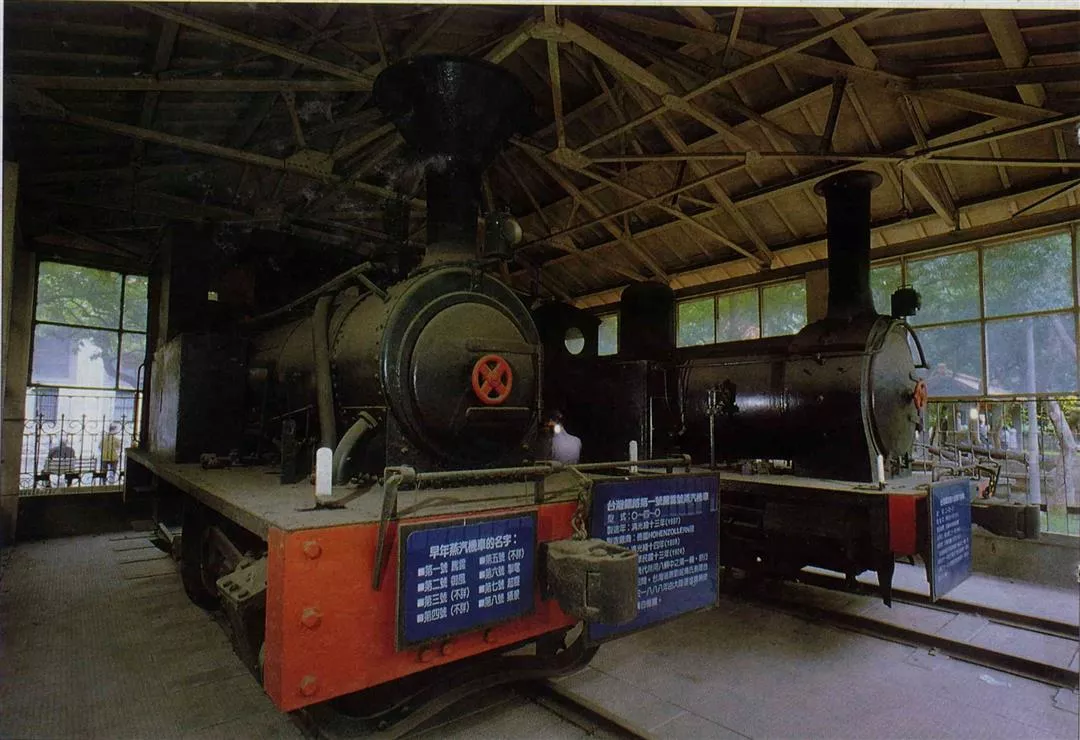

Liu Ming-chuan was the first man appointed governor of Taiwan after it gained provincial status. In his tenure he built a railroad from Taipei to Keelung, and this engine, called "Bounding Clouds," which now standsin Taipei's New Park, is from that era. (photo by Vincent Chang)

Taking an interest in Taiwan

In 1684, the Ching court adopted Shih Lang's suggestion and decided to make Taiwan part of the national territory. They made Taiwan a "Prefecture" with three separate counties. At the time, there were about 300,000 Han Chinese in Taiwan. On the one hand, the Ching authorities were generous toward the Cheng family, in order to win the loyalty of the local populace. On the other, they dispatched 10,000 troops to prevent uprisings.

Taiwan was combined with Xiamen, a city on the coast of Fujian Province, into a single administrative district. The highest Ching governing structure for Taiwan was called the "Taiwan-Xiamen Military Reserve Administration." Its highest ranking official, the "Administrator," was under the jurisdiction of the governor of Fujian Province. The administrator spent half of each year in Xiamen and half in Taiwan, handling both political and military affairs. The civil office under the administrator was called "Taiwan Prefecture," while the military office was called the "Taiwan Garrison."

When the Ching dynasty first acquired Taiwan, it showed little interest in the island. There was even talk of giving Taiwan up. Later on, despite the establishment of formal governmental offices, the Ching court's attitude toward Taiwan was merely "to insure that the island remained quiet and posed no threat," but they had little enthusiasm for positively developing the island. This attitude is evident in the continuing ban on mainland Chinese emigrating to Taiwan even after the integration of the island into the imperial bureaucratic system. (People got to Taiwan only because the law was not strictly enforced.)

After the Western imperial powers resorted on several occasions to blockading China's ports to pressure the government, the Ching court beganto pay more attention to the consolidation of coastal defenses. After a series of military defeats, in the 1870s the Ching initiated a program of Westernization and strengthening of the armed forces. Taiwan's administrators at this time included Shen Pao-chen and Ting Jih-chang. Shen strengthened the island's defenses and put up electric power lines, while Ting finished up Shen's projects during his own brief tenure. Also, being a Hakka himself, Ting recruited large numbers of Hakkas to come to Taiwan to settle. Regrettably, Ting had to return to the mainland after only a year because of illness.

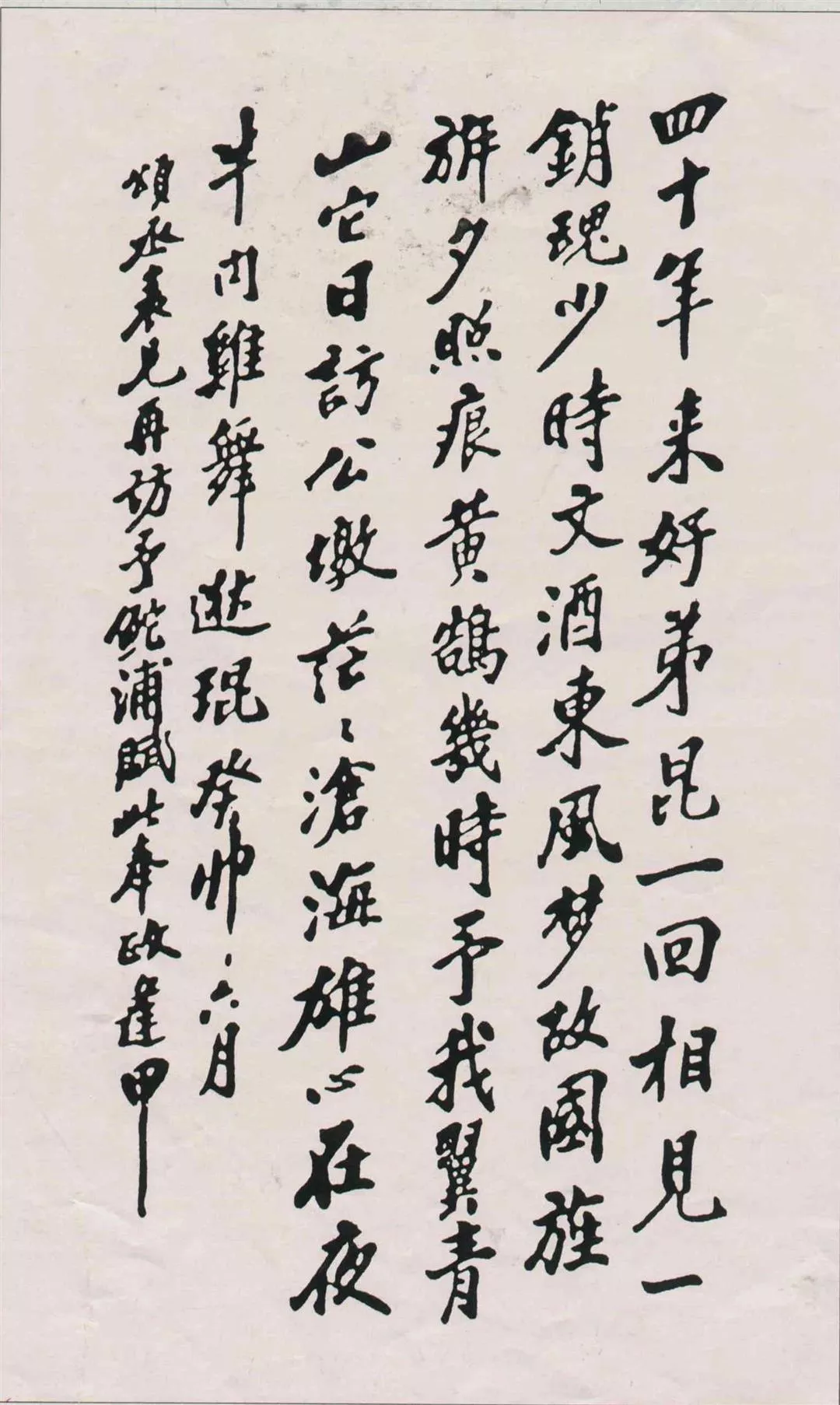

Chiu Feng-chia, a Ching-era Taiwanese intellectual who led forces resisting the Japanese, wrote sorrowfully during those times, "The prime minister has the power to slice off a piece of the nation, and as a single subject, I have no means at my disposal to remedy the situation." This is another of his works of calligraphy. (courtesy of Chiu Hsu-nu)

Taiwan gets a provincial governor

In 1885, Taiwan was finally made a province in its own right by the Ching. Liu Ming-chuan, the first governor, was extremely dedicated, and made many important contributions to the construction of Taiwan. For example, he began railroad construction, opened academies of learning, established a postal service and a telegraph system, and constructed armaments factories, all of which hastened the modernization of Taiwan.

Liu Ming-chuan's achievements did not last long. His successor Shen Ying-kuei was little more than a transition figure, lasting less than a year. The next governor, Shao You-lien, arguing that it was necessary to reduce expenditures and give the people a rest, halted many of the projects pushed so actively by Liu. The academies of Western and aboriginal learning were closed, and the railroad was thought to be too difficult to maintain or extend. Thus ended Taiwan's brief period of innovative construction.

In 1894, on the eve of the Sino-Japanese War, Tang Ching-sung was dispatched as "acting governor" to take over administrative duties. But less than a year after his appointment, the defeated Ching court ceded Taiwan to Japan. Tang Ching-sung worked together with Chang Chih-tung, who was chief minister for South China Sea affairs and whom Tang regarded as his mentor, in hopes that they could get the Western powers to intervene and prevent Taiwan from falling under Japanese control. But, after Russia, Germany, and France succeeded in forcing a Japanese withdrawal from the Liaotung Peninsula in northern China, the Ching court was wary about reopening the Taiwan issue, so Tang was ordered to return to China and give up his plan. Tang had little choice but to obey, and prepared to leave the island.

However, Taiwan gentry led by Chiu Feng-chiarallied the soldiers and common people to resist the Japanese. They established the "Republic of Taiwan," and pushed Tang Ching-sung to be the president, compelling him to stay in Taiwan to lead the resistance against Japan. Caught in a difficult position, Tang chose to declare Taiwan "independent" on May 23, 1895; he organized troops to fight Japan, thus beginning the war for Taiwan.

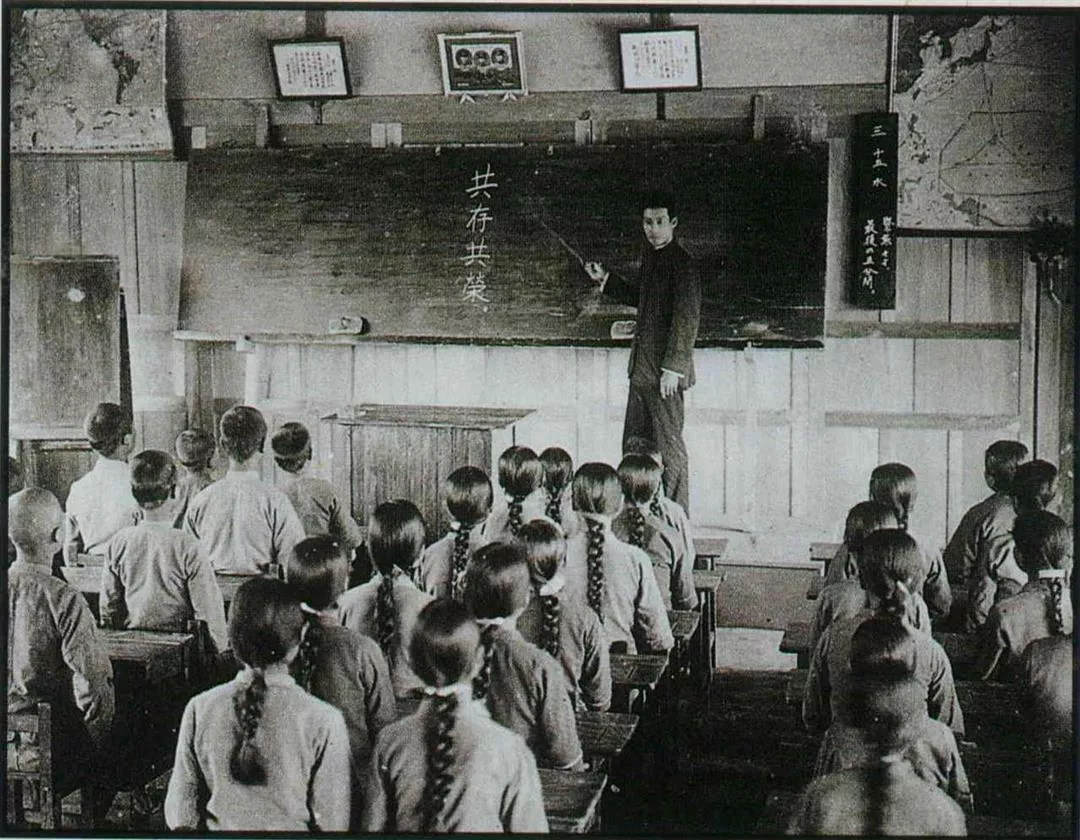

When full-scale war between China and Japan began in 1937, Taiwan became an important base and supply center for Japanese forces heading south.This made it important for the Japanese to ensure the loyalty of their Taiwanese subjects. The photo shows a teacher telling students about the ideal of "a common existence, a common glory." (photo courtesy of ChengMao-jen)

The short-lived "Republic of Taiwan"

At that time, the combined forces of Taiwan citizens and soldiers plus the garrison originally sent over from the mainland totaled about 50,000 men, mainly concentrated in the north. This hastily assembled force was only able to withstand attacks by the well-trained and well-equipped regular Japanese forces for about a week. The army collapsed, and Tang fled to the mainland.

Before Japan took over Taiwan, none of the rulers of Taiwan had actually extended their control over the whole island. The Dutch and the Cheng family simply held a series of strongpoints, while the authority of the Ching was limited to the western plain and a small part of the east coast. The mountain areas, inhabited by indigenous peoples, were not under central government control. In fact, we can get an idea of the Chinese concept of their territory in Taiwan from a map made during the Tung Chih reign (1862-1875) of the Ching dynasty: The map only has the western part of Taiwan; the eastern part isn't even drawn in!

The Japanese were the earliest to exert effective authority over the whole island, and they were the first to have a comprehensive plan for Taiwan. They established a legal system, founded modern schools, developed the railroad system, and undertook complete censuses and land surveys. These programs were connected to the political plan Japan had for its colony: Japanese leaders felt that Taiwan occupied an important strategic position astride the East and South China seas, and the navy was especially anxious to exert effective control over Taiwan and the Pescadores.Not only did they want to build Taiwan into a base for further military expansion, they hoped to squeeze the colony for its economic resources (such as sugar) to support capitalist economic development in the mother country. A certain level of construction in Taiwan was part of this concept of economic exploitation.

For both Han Chinese and indigenous peoples, the Japanese were clearly a colonial regime. This is reflected in the fact that the selection of the governor followed not local concerns, but political trends in Japan proper.

The flags flutter in the wind. What kind of era will Taiwan enter after the first popularly-elected governor in history takes office? (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Like an emperor

The chief Japanese official in Taiwan was called the governor-general. Nineteen different men served in the position. Having had no previous colonial experience, during the course of negotiations with the Ching dynasty the Japanese invited foreign specialists and their own navy's "Taiwan experts" (including Kabayama Sukenori, the first governor-general) to draw up a political program for the colony. This program made the governor-general the highest authority on the island. He could issue decrees and command military forces. He was, in a sense, the Japanese emperor in Taiwan.

The 50-year Japanese occupation era can be divided into three parts depending on the main policy adopted toward Taiwan: the period of military rule (1895-1919), the period of civilian rule (1919-1936), and the period of the war between China and Japan (1936-1945).

From the first governor (Kabayama) through to the seventh (Akusi Genziro), all were military officers. This is connected to the ongoing "pacification" policy in the early years of Japanese rule. In this 24 year period, the military and police attempted to assert control. The Japanese established a tight bureaucratic and local administrative structure in order to pursue their policies. The administration was divided into four levels: province, department, city (or prefecture), and neighborhood (or village). All were controlled by Japanese police, and Taiwanese had no right to participate in politics at all. Taiwan was governed under the "6-3" law, which empowered the police to detain citizens. Moreover, since the strongest resistance to the Japanese military had come from the small towns and villages of south and central Taiwan, the Japanese instituted a "collective responsibility" system to control those areas: if anyone committed a crime, all of those in the same unit (consisting of ten households) would also be punished.

Activities by anti-Japanese guerrillas created considerable difficulties for the first four governors-general. In 1902, the director of the Bureau of Civil Affairs, Goto Shinpei, who was in day-to-day control of the colonial administration because the nominal governor-general (Kodama Gentaro) concurrently held a post in Tokyo, frankly admitted that in the five years since his posting in 1898, the colonial authorities had killed more than 11,000 "rebels." The total number of Taiwanese killed in the eight years from the beginning of the occupation through 1902 was over 32,000. This was more than one percent of Taiwan's population (which was about 2.8 million people at that time.)

The Japanese tried resistance fighters using the "Decree on Crimes by Bandits," which enabled the government to impose severe penalties and brand resisters as criminal elements. Retaliation for anti-Japanese activities led to the deaths of countless Taiwanese. With no outside support, the resistance movement gradually collapsed.

From subjugation to assimilation and back

Taiwan's first civilian governor-general, Den Kenziro, arrived in 1919. From that time until 1936, there were nine successive civilian chief executives, the last being Nakagawa Kenzo. This 17-year period coincided with the period of "Taisho democracy" in Japan. The policy toward Taiwan changed from one of "subjugation" to one of "assimilation."

Under the assimilation policy, the Japanese issued the Taiwan education law, eliminated differential education, implemented the common study system, recognized improperly documented marriages, set basic principles for internal governance, and more. However, though the stated policy was to "treat Taiwanese as compatriots, as if they were Japanese," the policy operated more in theory than in practice. Not only was the "6-3"law in force for the full 50 years, not for one day was Japan's own constitution extended to Taiwan. And later, under the "Japanification" movement (literally "the movement to make Taiwanese into full subjects of the Emperor"), Taiwan's language and traditional cultural activities and religious beliefs were all banned or restricted.

The 17th governor-general, Kobayashi Seizo, was a retired admiral. His accession to the post in September of 1936 indicated that Japan had again changed its policy toward Taiwan, returning to the practice of ruling Taiwan through military officers. The reason was none other than that they were preparing for aggressive war.

All remaining governors-general, right down to Ando Toshikichi, the governor at the time of the Japanese surrender, came out of the military.All rigorously enforced the "Japanification" policy. But they were unable to escape defeat in the war, and Taiwan finally came into the hands of the government of the Republic of China.

The Office of the Governor-General became the "Office of the Governor for Taiwan Province." The last Japanese governor-general--after sending home more than 450,000 Japanese soldiers and civilians--was arrested for war crimes and sent to Shanghai to be tried. There he later committed suicide, marking an end to his own controversial life and adding a final postscript to 50 years of colonial rule.

After being returned to China, Taiwan was kept apart and given a special status because the mainland had not returned to a state of normalcy. Administration was placed in the hands of a single "hsing-cheng chang-kuan" appointed by the central government. This term is generally rendered into English as "governor," but its literal translation is "chief executive official." Meanwhile, other aspects of life in Taiwan--such as the currency, rationing, and so on--were also different from the mainland.

The first--and only--governor to serve under the title of "chief executive official" was General Chen Yi. It was during his administration that the "February 28 incident" --riots by Taiwanese directed at people and officials from mainland China--occurred.

There are many different theories as to the causes of the February 28incident, and no consensus has yet been reached. Some place blame on errors made by the incoming administration--poor discipline among the troops or bad economic policy. Some think it was due to a conspiracy among Taiwanese communists at that time, who took advantage of the situation to drive society into chaos. Some scholars theorize that with two different systems separated for such a long period of time, once reunited, a crisis of adjustment was inevitable. But whatever the causes, Chen Yi, as the highest ranking administrative official, can not deny responsibility.

Looking at economic policy, Chen's response to the economic crisis and the food shortage was to establish a monopoly bureau and a trade bureau, and to centralize the distribution of goods. This led to a flourishing black market and hyper-inflation.

Exacerbating the situation was the fact that at the beginning of 1947, the economy in mainland China was on the brink of collapse. The public disturbance over the instability of Shanghai's gold dollar had an impact upon Taiwan's currency values and prices. Businessmen took advantage of the situation to start hoarding commodities, which led to food shortages. On the eve of the February 28 incident, a dangerous tension already hung in the air.

The February 28 tragedy continued until March 17, when Defense Minister Pai Chung-hsi arrived under orders to pacify the situation, and things gradually quieted down. But this incident has had a far-reaching influence that is only now slowly healing. Following the incident, the central government, according to the investigation report by Pai Chung-hsi, began to instigate reforms, one of which was changing the structure of the governor's office.

The civilian official Wei Tao-ming was named the first governor under the new system. Importantly, while the new position, like the old, has always been translated into English as "governor," in Chinese the new position has a vastly different name: sheng chu-hsi, which translates literally as "chairman of the provincial government."

When Taiwan shifted from the "chief executive official" to the new system, the Law for the Organization of the Provincial Government stated that there should be one governor (sheng chu-hsi), to be nominated by the Cabinet, to be approved by the Taiwan Provincial Assembly, and to receive his appointment formally from the president. Although in theory the government had changed from a system with a single leader to a "committee leadership system" (for, technically speaking, the governor was merely the chairman of a large committee of "provincial commissioners"), in practice the system functioned with a single leader.

Meanwhile, in order to win public support, the agencies of the provincial government were headed by Taiwanese. However, shortly thereafter mainland China fell to the Communists, and retreating soldiers and refugees flooded into Taiwan. Taiwan again entered a period of great tribulation.

After moving to Taiwan, the central government reassessed why the mainland had fallen to the Communists so suddenly, and decided to undertake a thorough reform.

Chen Cheng, a general, was the second governor under the sheng chu-hsi system. After he resigned to become Political and Military Administrator for Southeast China, he was succeeded by K.C. Wu, a civilian with a PhD in political science from Princeton University in the US, who was appointed to win favor from the Americans. In his tenure Wu actively promoted Taiwanese in order to win the support of local elites. Three of the five directors of department level offices were Taiwanese, as were 17 of the 23 provincial commissioners, which was unprecedented for that time.

Land reform consolidates the foundation

The Communists were able to take advantage of the Nationalist government in mainland China mainly due to a disparity between rich and poor, which was in turn blamed on the landlord system. One of the first policies adopted after the move to Taiwan was land reform. This was a three step program, begun under Chen Cheng, which included the "37.5% rent limitation," the "sale of public land to farmers," and the "land-to-the-tiller" policies. Not only did this bring about far greater equality in the distribution of land, thus winning the support of farmers for the government, it also unlocked the capital frozen in land and compelled former landlords to reinvest their compensatory money in industry. This led indirectly to the economic takeoff and the "Taiwan experience" as it is known today.

The fourth and fifth governors (Yu Hung-chun and C.K. Yen, respectively), were experts in economics and finance. Continuing the policies of the past, in this period they worked to consolidate the foundations for economic growth. They placed emphasis on balancing the budget and also on food policy. Believing that "if staple foods are stable, the economy will definitely be stable," they initiated the "fertilizer for grain" system and the purchase of surplus grain. Both men fulfilled their responsibilities.

The next three (sixth through eighth) governors--Chou Chih-jou, Huang Chieh, and Chen Ta-ching--who covered the period 1957 to 1972, were all career military officers. This was clearly related to the escalation in tension with Communist China in those days.

In this period, the Central Cross Island Highway and the Shihmen and Tsengwen reservoirs were all completed. Nine-year compulsory education was implemented. Land reform continued: Farmland was rezoned and "equalization of urban land rights" put into effect. These laid the foundations for the transition from being a developing to being a developed country.

Taiwanese take the lead

In June of 1972, Hsieh Tung-min became the ninth governor. He was the first Taiwanese to hold the position, and was also a civilian. This indicated that the government was turning its attention toward domestic development and toward more active promotion of local level construction and social welfare. Thus, for example, when Lee Teng-hui became governor, he initiated the "Agricultural Army of 80,000" campaign, which aimed to rescue the countryside from slow disintegration and to upgrade the levelof agriculture. It was in these years that the Taiwan economy began to truly take off, leading to the "economic miracle."

The next four governors--Lin Yang-kang, Lee Teng-hui, Chiu Chuang-huan, and Lien Chan--are all elite politicians of Taiwanese origin. Their appointments reflect the implementation of "Taiwanization" of government at all levels, and the systematic cultivation of Taiwanese political talents to develop in them the right abilities to succeed to top positions.(All four men have gone on to major roles in the central government.)

The 14th governor to serve under the title of sheng chu-hsi (or "chairman of the provincial government") is James C.Y. Soong. He has been the key player in the transition from the old system to the new. During his term, the government, in order to fulfill promises made to the electorate, passed the "Law on Self-Government for Provinces, Counties, and Cities." Under the new law, the provincial governor (now called the sheng chang, which literally translates as "head of the provincial government")is to be popularly elected, which will reflect the will of the people. (Indeed, he will already have been elected by the time you read this article!)

Taiwan has seen 164 different governors--with various titles representing the imperial, colonial, and republican systems--come and go. They have had great significance in the history of Taiwan. Still, from the longer term point of view, the popular election of the provincial governor may be worth a whole book in itself by future historians.

[Picture Caption]

p.85

This early Japanese map of the "territory of the Ching dynasty" not only depicts Taiwan and the Pescadores in interesting shapes, it also includes fascinating historical notes.

p.86

"Fort Zeelandia," built by the Dutch in the 17th century, had full defenses; the fort held out for a year before surrendering to besieging forces under Chinese general Cheng Cheng-kung.(courtesy of the Southern Meterials Center)

p.87

Fort Zeelandia was renamed Fort Anping. The history of 400 years of governing in Taiwan is left behind in both the written word and historic artifacts.

p.88

Liu Ming-chuan was the first man appointed governor of Taiwan after it gained provincial status. In his tenure he built a railroad from Taipei to Keelung, and this engine, called "Bounding Clouds," which now stands in Taipei's New Park, is from that era. (photo by Vincent Chang)

p.90

Chiu Feng-chia, a Ching-era Taiwanese intellectual who led forces resisting the Japanese, wrote sorrowfully during those times, "The prime minister has the power to slice off a piece of the nation, and as a single subject, I have no means at my disposal to remedy the situation." This is another of his works of calligraphy. (courtesy of Chiu Hsu-nu)

P.92

When full-scale war between China and Japan began in 1937, Taiwan became an important base and supply center for Japanese forces heading south.This made it important for the Japanese to ensure the loyalty of their Taiwanese subjects. The photo shows a teacher telling students about the ideal of "a common existence, a common glory." (photo courtesy of ChengMao-jen)

P.94

The flags flutter in the wind. What kind of era will Taiwan enter after the first popularly-elected governor in history takes office? (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)