Building with Bamboo:

The Revival of Traditional Indigenous Techniques

Cindy Li / photos by Kent Chuang / tr. by Scott Williams

September 2024

Taiwan’s indigenous peoples have traditionally had an exceptionally close connection to bamboo, using the plant for everything from food and clothing to housing. These links are particularly evident in their architecture: they have hundreds of years of accumulated experience building bamboo structures that embody their spirit and culture.

Located within Beinan Cultural Park, a meeting house for young people, called a ttakuban, overlooks fields once tilled by the residents of Puyuma, a Pinuyumayan indigenous community in Taitung City.

“A ttakuban is both a communal building and a school for young men. We all studied in one while growing up.” Village elder Ahung Masikadd stands in front of the ttakuban, which he built a few years ago with the young people of the village, while he explains the significance of the bamboo stilt-house structure.

The root of Pinuyumayan strength

The Pinuyumayan have long been a strong and prosperous people. Research has linked those traits to the strict social hierarchy established by the ttakuban educational system.

Ahung Masikadd says that 12- and 13-year-old boys used to build a ttakuban from makino bamboo (Phyllostachys makinoi) and spiny bamboo (Bambusa spinosa) under the guidance of elders. They would then live there for the next four or five years learning rules and customs, social hierarchy, fighting skills, and how to interact with others from older boys who entered the ttakuban before them.

“Outsiders often found what we taught to be weird or even illogical,” says Ahung Masikadd. But he believes that this training was an important part of the process of turning Pinuyumayan boys into adults.

Before leaving the ttakuban, the youths would pass through the mangamangayau (“intense training”) ritual, also known as the Monkey Ritual, an important rite of passage usually held in late December.

On the eve of this event, the boys would go from house to house holding banana leaves and shouting “Abakayta! Abakayta!” (“Fill up my pouch!”) to drive out evil spirits. Traditionally, on the next day the boys would use spears carved with tribal symbols to kill a monkey they had spent much of the previous six months with and regarded as a friend, in the hope that they would show the same resolve when protecting their homes and lands on the battlefield. Nowadays, they use a monkey effigy.

Ahung Masikadd stresses: “Mangamangayau has to held before the many other ceremonies that follow can be performed.” One of these is mangayaw, a three-to-five-day-long hunt and patrol of the village’s territory that involves all of the males in the community. After they return, there is another ceremony in which young people “open the door” for families in mourning in that year.

Ahung Masikadd solemnly explains, “The ttakuban is the foundation for training warriors, the ridgepole supporting our nation, and the locus of Puyuma’s spirit.”

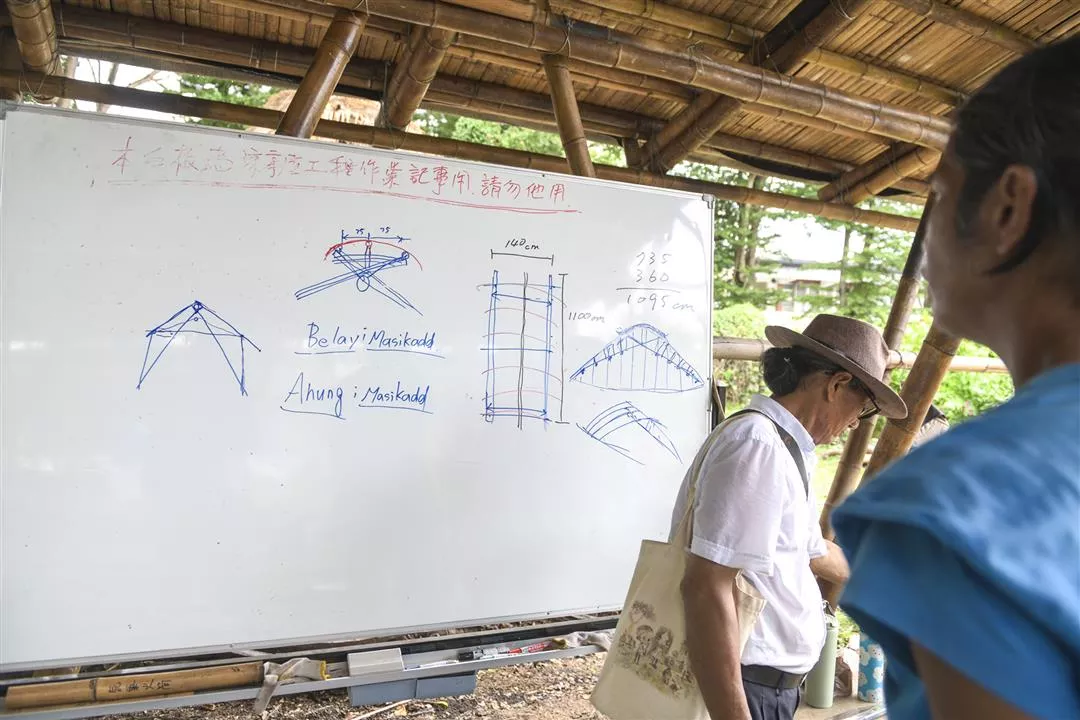

Ahung Masikadd and his son Benglay Masikadd building a bamboo structure at Nanwang Puyuma Wreath Experimental Elementary School.

Construction and culture

Architect Lin Yayin says that the Puyuma Village ttakuban has a number of unique structural features. For example, the libattubattu is a core load-bearing structure located at the center of the building’s base, and the panubayun are angled supports that radiate from the roof beam to the ground in eight directions.

Lin says that buildings reflect an ethnic group’s spirit and philosophy. The word panubayun connotes “uniting,” and the actual angled supports come from all directions to gather at a point and provide stability.

Lin adds, “The ttakuban is a light structure that is resistant to earthquakes but vulnerable to wind.” Builders increase the ttakuban’s stability by filling the conical libattubattu, which sits on the ground at the center of the structure, with stones that weigh the building down and lower its center of gravity. In fact, research by Taiwanese scholars has shown that the libattubattu functions similarly to Taipei 101’s tuned mass damper, causing one scholar to exclaim: “Taiwan’s Aborigines are natural-born scientists!”

This design enabled the flimsy-looking bamboo building to remain standing through 2016’s Typhoon Nepartak, which had windspeeds of more than 200 kilometers per hour. Lin laughs, “It’s because our ancestors understood so much more about natural materials than we do.”

She laments that Taiwan’s traditional construction techniques were not passed down to younger generations, and knowledge of natural construction materials gradually slipped away once reinforced concrete became the default choice. “We’re Taiwanese. We should learn Taiwan’s traditional construction methods, culture and handicrafts.”

Traditional construction methods were largely passed down from master to apprentice, and rarely written down. Designs and construction methods also tended to vary based on the builder’s understanding of techniques and view of the project. “I spent 20-some years learning from various elderly craftspeople. When each one passed away, the accumulated knowledge of generations passed away with them.”

Lin and Ahung Masikadd offer classes in the Lizen Education Foundation’s bamboo construction program. Their goal is to address the problem of the transmission of knowledge by systematically teaching ttakuban construction methods to students from all walks of life. They are also working together to document these methods.

In their as-yet-unpublished Puyuma Ttakuban: Traditional Bamboo Construction in Taiwan’s Puyuma Village, Ahung Masikadd relates the history, cultural significance and process of constructing a ttakuban, describing the latter in detail and illustrating it with photographs.

Lin says, “If I don’t write it down, the knowledge will be lost when this generation passes.”

Lin Yayin and Ahung Masikadd teach a Puyuma bamboo construction course through the Lizen Education Foundation. (photo by Wu Jiayou, courtesy of Lizen Education Foundation)

Lacking a background in architectural drawing, Ahung Masikadd teaches his bamboo construction methods using simple illustrations.

When teaching ttakuban construction, Lin Yayin asks students to use indigenous names for building techniques and features. (photo by Yang Xiaohong and Cai Zhuolin, courtesy of Lizen Education Foundation)

Ahung Masikadd’s efforts to revitalize Puyuma Village’s culture led to the addition of a ttakuban and painted tribal motifs on the school’s eaves.

Bamboo’s importance wanes

“For the Atayal, bamboo is a construction material that’s right at hand in their environment,” says Shan Shih-hsuan, an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at Ming Chuan University.

Taiwan’s geography and climate allow bamboo to grow everywhere from the plains to the mountains, making it an easily accessible building material for Taiwan’s indigenous peoples. In traditional Atayal culture, men were expected to be able to weave ruma (makino bamboo), while women were not permitted to learn how. These days, many of Taiwan’s kitchen utensils, agricultural frames, and aquacultural oyster frames, as well as the kendo swords we export to Japan, are made of bamboo and closely connected to the Atayal’s makino bamboo industry.

But with the passage of time the relationship between bamboo and Taiwanese Aboriginal cultures, including that of the Atayal, has grown tenuous. “Nowadays the buildings in villages look just like those on the plains.” He sighs and says that the homogenization resulting from urban expansion into rural communities has made reinforced concrete buildings the landscape of Taiwan. Villages have lost their cultural DNA in a way that’s similar to the decline of the bamboo industry.

Following in the footsteps of former Taishin Financial Holdings president Lin Keh-hsiao, Shan created a “mountain architecture” course at Ming Chuan that takes students to Atayal villages across Northern Taiwan, where they construct bamboo buildings in hopes of helping the communities recover their lost culture.

Shan and his students have carried out a whole series of projects using the makino bamboo the Atayal know well to create bamboo structures including 2011’s Atayal Hunting Trail cultural gallery in Yilan’s Kngungu Village, 2013’s conservation and exhibition center for Swinhoe’s pheasant (Lophura swinhoii) in Taoyuan’s Piyaway Village, 2017’s Melihang Workshop construction plan in Mepuwal Village by Miaoli’s Da’an River, 2019’s reading nook at Taoyuan’s Kuihui Elementary School, and 2020’s Bamboo Construction Co-creation Program in Taoyuan’s Qapu’ Village.

The bamboo supports of the ttakuban’s lower section also have a defensive function. (photo by Yang Xiaohong and Cai Zhuolin, courtesy of Lizen Education Foundation)

Ahung Masikadd has been slowly reviving Pinuyumayan culture in his hometown.

Recovering themselves

“Our goal is to facilitate localism and autonomy by working with villages on building design and community development programs.” Shan stresses that no matter the project, he and his students are always aiming to create opportunities for communities to revive their culture.

These efforts have educational significance for the participating students, too. Shan shares that the students learn about tribal culture, hear stories from village elders, venture into bamboo forests to cut bamboo, and even learn the best times to cut bamboo. “It’s physically and spiritually enlightening for them.” He explains that it encourages modern-day students, who are typically never without their cellphones, to begin to have real conversations with the people in those communities.

“Spaces” acquire significance and become “homes” via the lives, rituals, beliefs and other cultural trappings of those who live in them. Shan says: “We are giving spaces back to people so that when they return to their villages, they can feel at peace and connected to their culture there.” These bamboo structures aren’t just buildings, they are villagers’ hometowns and a locus for centuries of Aboriginal culture.

-14.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Shan Shih-hsuan (center), an architecture professor at Ming Chuan University, takes students into the mountains to help Atayal villages recover their traditional bamboo culture. (courtesy of Shan Shih-hsuan)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)