Checheng

An Old Logging Town Reborn

Cathy Teng / photos by Kent Chuang / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

April 2025

Surrounded by mountains, Checheng is located in Nantou, Taiwan’s only landlocked county. As the terminus of Taiwan Railway’s Jiji Branch Line, the town is also known as “the end of the line,” but it isn’t in fact all that remote. When the sugar, logging and power-generation industries flourished in surrounding areas, it became something of a transportation hub. In recent years, the tourism industry has taken off here, revitalizing the town and giving it a chance to shine a spotlight on its history.

From Taipei, we take the high-speed rail to Taichung’s Xinwuri Station, where we transfer to TR’s Western Trunk Line. We get off at Ershui in Changhua County and transfer to the Jiji Branch Line, which takes us to our ultimate destination, Checheng. Upon alighting, we are greeted by a view of the massive Mt. Songbailun and the serene emerald waters of the town’s old timber storage pond. As sunlight filters through bald cypress trees onto the lakeside trail and its Japanese-era buildings with their dark wooden siding, the fatigue of our journey melts away amid the charming atmosphere and picturesque scenery. It is no wonder that this small town attracts tourists from far and wide.

Industries’ rise and fall

The Chinese characters for Checheng mean something like “car plaza.” During the era of Japanese rule, the colonial government put its primary focus on extracting Taiwan’s natural resources. Sugar in particular was a major export. To bring out the sugar produced by the sugar refinery in Puli, the government built a push-car railway line from Puli via Checheng to Ershui, where the sugar would be loaded onto trains on the Western Trunk Line. Because Checheng was surrounded by a broad area of relatively level land, it became a key relay station and a storage site for rail push-cars. At times more than 100 cars were parked here. Hence, the Taiwanese came to call the spot Checheng.

Light industry was the Japanese government’s next target for Taiwan’s development, and for that power generation was essential. The government was eyeing the Sun Moon Lake area for hydropower, and it ended up selecting Menpaitan as the site of its first hydroelectric dam hereabouts, later renamed the Daguan hydroelectric plant. To transport heavy equipment and generators to this location, in 1919 they began work to widen the original push-car railway from Ershui via Checheng to Daguan, turning it into a regular railway. That was the origin of today’s Jiji Branch Line.

After the electric plant was completed, management of the railway was transferred to the colonial government’s Railway Department and it became a regular operational line. With this convenient connection to the world beyond, the surrounding area, including Puli, was no longer isolated, and rice, sugar and other local products began to be shipped out via Checheng, while goods from the outside were brought in. The town became an important transportation hub.

Two overhead cranes that were used to move logs remain in place today and are likewise fixtures in the memories of townspeople.

Checheng became a transportation hub thanks to the area’s booming sugar, power-generation, and lumber industries.

In Checheng’s compact old quarter, the air still carries the fragrant scent of wood.

The logging era

As well as consulting historical documents about Checheng, we interviewed Lucille Sun, chief supervisor of The Grove, a tourist retail center in Checheng, and granddaughter of the founder of Chen Chang Lumber Industry, to learn about the rise and fall of the wood industry here.

Sun’s grandfather Sun Hai was born in Yunlin’s Kouhu Township, and in his youth he went to work on Mt. Ali before opening a wood-treatment plant in Chiayi. Then in 1958 he placed a winning bid with the Forestry Bureau’s Luanda Forest District Office to log Compartment No. 8 of the Danda Forest District.

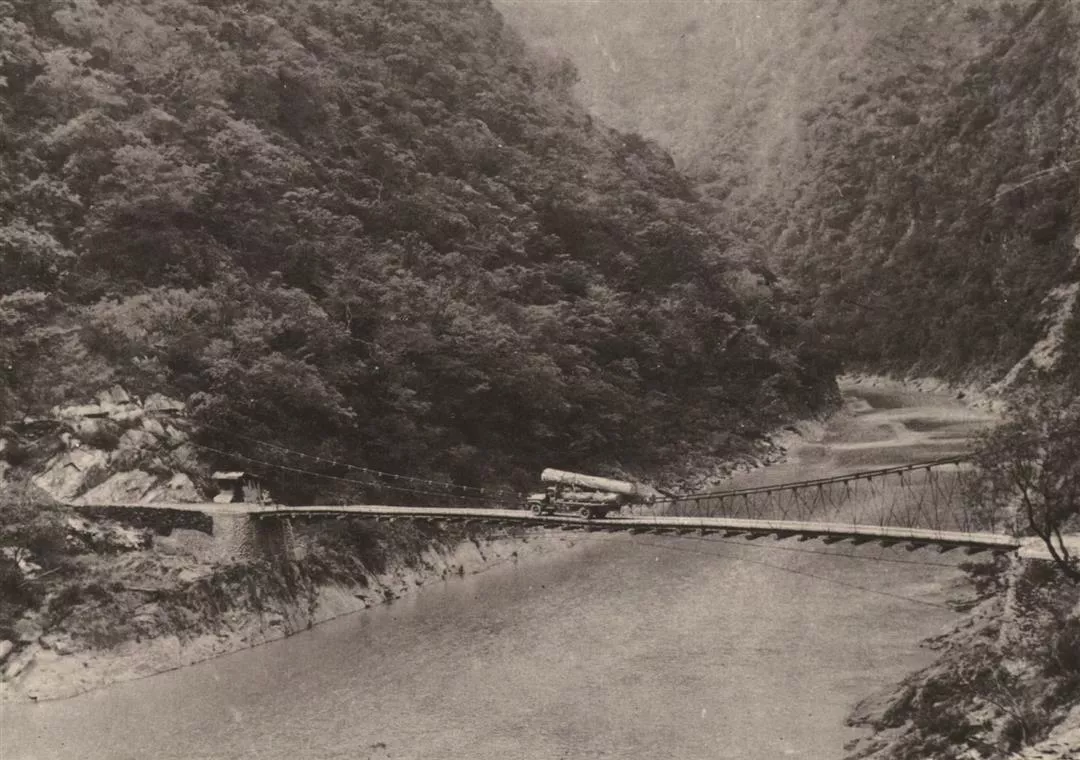

“Back then, Grandpa could see Checheng’s geographical advantage: Timber coming down the mountain could be put on trains here,” Lucille Sun explains. “So he bought land to build a wood treatment factory.” It was an era when Taiwan was relying heavily on forestry products to earn foreign exchange, but felling trees wasn’t easy money. Lucille, who was born in the late 1970s, may not have experienced that era for herself, but from the stories she has heard from oldtimers and the photographs she has seen, she has been able to piece together what the logging life was like back then. “The doors of the trucks transporting the logs were all removed—not for simple convenience, but so workers could jump out quickly in case of an accident.”

Chen Chang started out with an emphasis on treated wood, producing telephone poles and railway ties for export. Later, it expanded into milling and processing lumber in various ways and exporting those products to neighboring countries. It is most famous for the wood it produced for the grand torii gate of the Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo. Even today, visitors to the shrine see a sign noting that the gate’s wood came from Taiwan’s Danda Forest District.

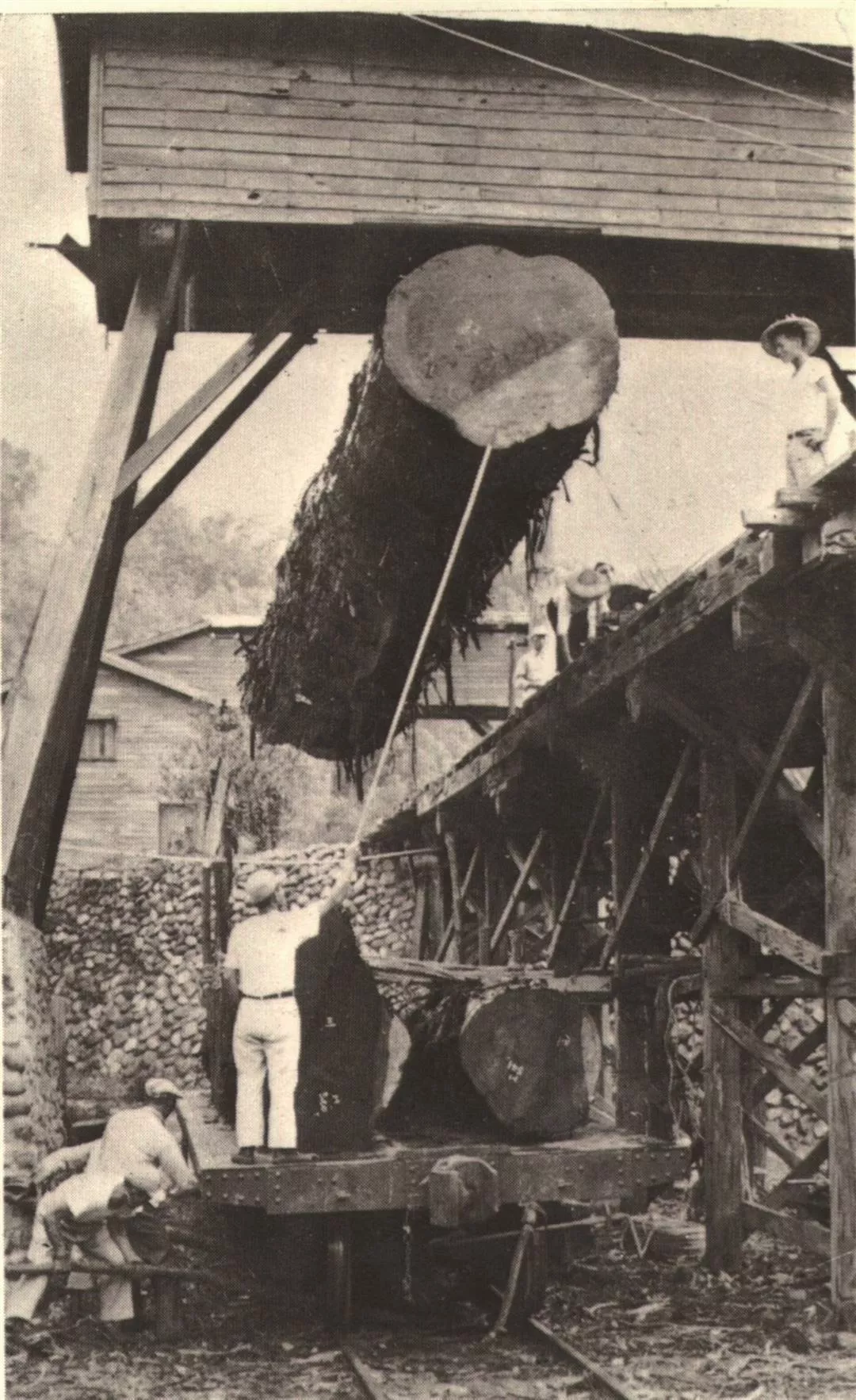

Old photos recall a time of felling timber, transporting lumber by steam train, and braving dangerous conditions on Danda Forest roads. (courtesy of Chen Chang Lumber Industry).

Old photos recall a time of felling timber, transporting lumber by steam train, and braving dangerous conditions on Danda Forest roads. (courtesy of Chen Chang Lumber Industry).

For the 90th anniversary of Chen Chang, all manner of items connected to the local lumber industry were put on display. They help visitors to better understand Checheng’s past.

For the 90th anniversary of Chen Chang, all manner of items connected to the local lumber industry were put on display. They help visitors to better understand Checheng’s past.

Lucille Sun has helped to turn Checheng into a town that attracts visitors from near and far.

After tragedy, revival

The small town flourished along with the lumber industry. Back then some 60% of the households in Shuili and Checheng relied on Chen Chang for their livelihoods.

But in 1985, Taiwan’s forestry policies changed, with a prohibition on cutting trees in natural forests, and the company turned toward processing imported wood from the South Pacific and Africa. Checheng lost its geographic advantage, and as the lumber industry withered, the town faced an exodus of residents.

The Jiji earthquake of September 21, 1999 was a major turning point for Checheng. With Central Taiwan suffering major damage, the central government decided to create the Sun Moon Lake National Scenic Area (SMLSA), and neighboring Checheng was placed within its administrative zone.

The Sun family sold some of their real estate, including the old sawmill building and the timber storage pond, to the SMLSA. The family themselves opened The Grove retail center, created a DIY experiential factory, and began selling meals of Dongpo Pork, Grandpa Sun Hai’s favorite, in wooden pails. “It used to be that only people buying and selling timber would come to Checheng,” says Lucille. But with the central government’s assistance, Checheng has gradually gained notice as a tourist destination on the Jiji railway line, ushering in a new golden era for the small town.

An old building that was part of the Chen Chang sawmill compound has been turned into Steam, a waterside restaurant. It’s a good place to enjoy a pot of tea and soak in the town’s charming mountain scenery.

Presented in a wooden pail as the star of a set meal, Dongpo pork, a favorite of Sun Hai, has become a Checheng speciality.

In the footsteps of the lumber industry

Lucille Sun guides us through how lumber used to be processed here. “Crane No. 1 would unload the logs into the timber storage pond,” she explains. When selecting logs, customers would get on top to assess their condition by rolling them, she continues. It was tiring and time consuming, so they would rest and drink tea in an adjacent wooden building. “It has been turned into Steam, a waterside teahouse.”

Steam has expansive picture windows, offering painterly views of the pond and a walking path constructed by SMLSA. A wonderful place to enjoy the changing seasons, the spot has become a favorite spot for social media shots.

What is today the Checheng Logging Exhibition Hall was formerly Chen Chang’s sawmill building, which, having been out of use for many years, was tilting and in danger of collapse. After the SMLSA took charge of it, the famous Taiwanese architect Kuo Chung-dwan and his firm Laboratory for Environment & Form were hired to renovate the building in a manner that would pay homage to its industrial past. The old mill’s framework is supplemented with a new structure, creating an interesting interplay of old and new wood construction within the same space. Reclaimed old timbers have been restored and reused, giving visitors insights into the evolution of building materials over half a century.

The Checheng Logging Exhibition Hall shows how logs were sawed and processed.

The mill’s old wood drying kiln has become an exhibition space that imparts knowledge about the lumber industry.

The green exterior walls of The Grove blend in with the surrounding green hillsides, and the orange is a nod to the paint that used to be applied to logging machinery to keep it from rusting.

Wasting nothing

Walking farther, we reach the area where they used to make various lumber by-products, such as essential oil and sawdust briquettes. Today it has become an experiential DIY space. Sun explains that her grandfather was an extremely frugal person who treasured natural resources and felt that they had to make use of 101% of logged wood. For instance, there are different ways to cut logs: There is the plain-sawn method, where the saw cut is parallel to the growth rings. This method yields more boards and produces less waste. But early on the Taiwanese wood industry took their cues from the Japanese, who favored quarter-sawn lumber. That method employs angled cuts that make the boards less prone to warping but create more waste. They then worked out how to extract hinoki oil from the waste wood, and the oil was exported.

The remaining waste sawdust was processed into briquettes, to be used as fuel. Faculty and students from forestry departments at various universities used to visit Checheng, enjoying the town as a living industrial museum and learning from Chen Chang how to maximize the use of wood.

Sun diligently asked her elders detailed questions about the lumber industry, hoping to gain a more complete historical understanding. Some of her interviewees regarded these matters as trivial and unworthy of memorializing, but she believes that “although society may hold a negative attitude toward the logging that was done back in the day, it is in fact part of our history. What I want to do is to uncover facets of Taiwan’s past so that everyone can better understand it.”

The town’s abandoned elementary school has become The Grove–Platform, a center for artistic creation.

A large piece by the up-and-coming graffiti artist Mar2ina has become a favorite backdrop for Instagrammers.

Bearbrick figurines attend a music lesson in one of the classrooms.

A beautiful transformation

As the marketing director of The Grove (Linbandao in Chinese), Lucille laughs that she is often called “Miss Lin,” since lin, the character for forest, is also a common family name. She is quick to clarify and impart a little forestry knowledge. “In fact, linban refers to a ‘compartment’ or section of forest to be logged.” So she picked those two characters as a way of commemorating her grandfather’s spirit. “Dao,” which means “way,” was chosen in the hope of finding a new way forward for the community.

In 2008, she had just completed a music program in the United States, and her father asked her if she would be willing to come back home to work. “At the time, he just wanted me to open a souvenir store. Despite being a total newbie to business, she decided instead to operate a full-fledged retail center.

The Grove has been up and running for more than ten years. In 2022, Lucille leased part of the former Checheng Elementary School to establish The Grove–Platform. She has positioned the space as a cultural promotion platform, to be used for activities such as exhibitions or artists’ residencies. “We can take advantage of the fact that so many people from various walks of life visit Checheng to show these artists’ works to more people.”

A colorful and expansive piece of graffiti on an outside wall by the artist Mar2ina, who was invited to Checheng by The Grove and Louisa Coffee, has become a popular spot for social media photos. In a hallway of the school, a piano, originally purchased for Lucille’s mother’s dowry, has been left out for public enjoyment. From time to time, the space resounds with visitors’ improvisations at the keyboard. Several classrooms have been turned into exhibition spaces, and artists of various stripes have been invited to exhibit. In one classroom Bearbrick figurines attend a music class.

Sun has a vision of what Checheng might become after five to ten years of further efforts to nourish its cultural soil. “Could Checheng one day raise its artistic profile to the level of Naoshima Island in Japan’s Inland Sea, drawing many to make special trips here?” That is the hope that she holds for the town’s future.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)